Scenario 5: PATTERNS THAT PERSIST: Biodiversity As The Measure Of Healthy Human Food Systems

by Genomic Gastronomy

#Food System Regulation #AgriTech and Farming #Precision Agriculture #Biodiversity

Here you can explore in detail the future scenario. Opportunities describe a potential for innovation that this scenario unfolds, considering specific technologies, context of application and industry. Scenario narrative gives a description of the scenario provided by the artist. You can also watch a Video to dive into the future world of the scenario, where the artist will guide you through. Trends of the scenario explore the current trends and developments on which the scenario is based. And finally Elements of the scenario provide artifacts, objects, personas and other elements from the future to immerse and discover the scenario.

OPPORTUNITIES

There are opportunities for companies specializing in precision agriculture technologies that can monitor and manage the biodiversity of farms, food processors looking to adapt their supply chains to source more biodiverse ingredients and promote sustainable practices, companies creating platforms that connect various stakeholders in the food system, fostering a community around biodiverse and sustainable food production; organizations providing training and resources to farmers and communities to adapt to the new biodiversity-focused regulations and practices.

SCENARIO NARRATIVE

What if… Biodiversity became the main measure of healthy human food systems.

This scenario imagines that in 2033, the buzzword in every part of the food system will be biodiversity. Attempts earlier in the 21st century for food systems to be chemical-free or carbon-neutral had limited uptake and impact. The scenario suggests that in 2028, the European Commission approved quite radical legislation called Maximizing Biodiversity. Since then, the increase in agricultural and wild biodiversity has had a big impact on the food system, with tangible and measurable changes and impacts, both good and bad. The story follows a journalist named Max, who travels through Europe in 2033, where he meets various stakeholders affected by this European focus on maximizing biodiversity.

From radical fringe groups in remote areas to the largest ag-tech corporations, everyone is looking for ways to make kitchens, farms, and rural landscapes more biodiverse. Max is particularly interested in talking to the farmers and citizens who feel left behind by the new focus and the network of regenerative farmers and food producers who work to heal agricultural landscapes.

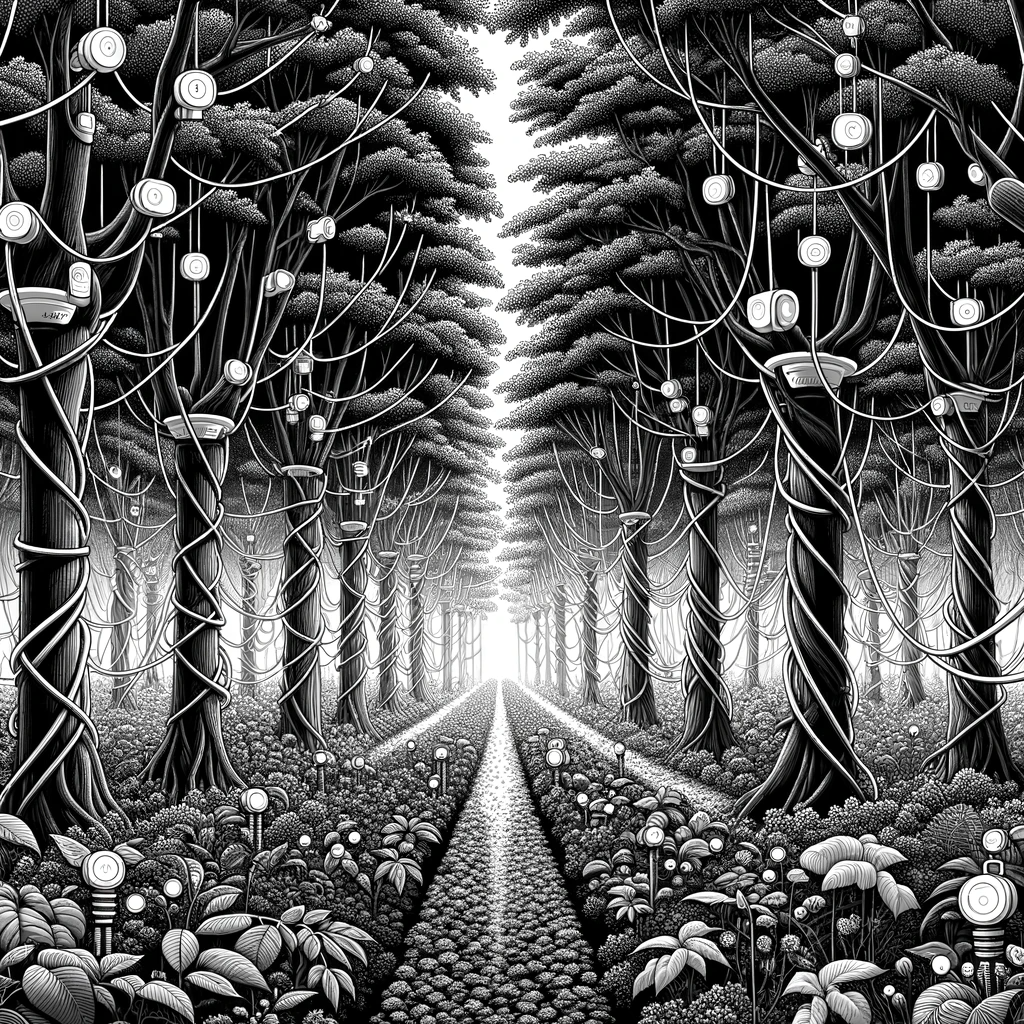

For example, in Poland, he speaks with a traditional farmer who struggles to adapt. As the farm adapts to new requirements, the less the farmer is sure what he is even farming. However, in Portugal, he meets a technician who designs monitoring tech for food forests, a pioneer in optimizing community-based emerging technologies for biodiversity and environmental healing. She has developed open-source DIY technologies that monitor the health and biodiversity of food forests, such as an AI-enabled audio ecology device and software and an online platform that connects producers with eaters. He also attended the filming of a talk show in Serbia about the future of food, where he observed that food is a playground for new possibilities and hybridities but also a battleground of polarised identity politics. Who do you think Max should visit?

VIDEO

TRENDS OF THE SCENARIO

TASTE OF PLACE

People don’t want to eat the same thing everyday or the whole year round. Different breeds of animals and cultivars of plants taste differently and perform differently in the kitchen. Maybe we shouldn’t eat bananas year round, or even at all if we don’t live near the tropics.

NATURE INCLUSIVE FARMING

The green revolution increased yields by breeding high yielding varieties, applying chemicals and rationalizing agriculture. It also led to massive environmental destruction and displacement or death of indigenous people and traditional foodways. Nature inclusive farming doesn’t simply attempt to put a price on ecosystems services, but tries to reintegrate natural organisms and processes regardless of their financial role.

NEW TECHNIQUES FOR MEASURING NATURE

In capitalist and enlightenment societies we only care about what we measure and we only measure what we care about. New instruments, tools and even epistemologies allow for more and more precise measurements of things.

DIETS, FARMERS AND IDENTITY

Farmers and rural communities in Europe are in revolt. Changing policies and economics are making it harder than ever to survive as a farmer. Debates about reducing meat and dairy consumption in the face of climate change are becoming one of the largest battlegrounds in the culture wars.

RESILIENCE, MITIGATION AND ADAPTATION TO CLIMATE CHANGE

Farms and food systems need to continuously adapt to the reality of climate change and prepare for the short and long term predictions. Most shifts in land use, cultivar mix and environmental management take years if not decades, but the climate emergency is today and goes through the next century.

GENETIC RESOURCES OLD & NEW

There are many institutions and communities preserving heirloom genetic material and creating new variations. Private, state and non-state actors contest each other for control of genetic resources in the agricultural sector.

TECHNOLOGIES FOR OPTIMIZATION AND EFFICIENCY

Robots, algorithms, AI and labs are all being used to optimize the creation of food products. These can take the form of alternative proteins, lab-grown meat, vertical farms and automated growing or milking operations that displace the human farmer all together.

ELEMENTS OF THE FUTURE SCENARIO

Person: The Technician

WHO: Inês

WHAT: Food Forest Technician

WHERE: Portugal

“I started out as a certified drone technician but now I consider myself a pioneer farmer, especially for the coastal landscapes of northern Portugal. In the early 2010s, I was working with satellites, sensors and drones. At the time, the obvious application for these technologies was in the military, but I soon saw a different opportunity.

I had inherited a neglected plot of land, so I began using technology to help me grow and monitor trees, plants and medicinal herbs. I thought it would be fun to mix traditional wisdom, modern technology, and community involvement to boost the biodiversity of our local food system.

I used drones to take multi-spectral images in order to assess the health of the landscape.

I developed an algorithm for helping with the complex task of timing and coordination when planting and harvesting a food forest.

The land is now a thriving food forest where we cultivate crops. I grow 200 species: all adapted to the changing climate conditions of the region.

Recently, I built bespoke technologies to measure the ecosystem services this landscape provides. This includes sensors for soil, water and carbon storage.

Now I’m even using an AI-enabled audio ecology monitoring system, to track biodiversity.

The data these tools collect and process is used to qualify for financial incentives, so I can afford to hire local people to do the delicate harvesting that robots can’t achieve.”

Person: The Teacher

WHO Katerina

WHAT: Teacher

WHERE: Netherlands

“I run an alternative school called the Resilient Century Academy (RCA). It’s located in the heart of the most densely populated country and technologically automated food economy in Europe.

While students in other schools are learning about prompt engineering and AI management, we have developed a curriculum that maximizes the amount of time that students spend outside in the neighborhood, working with their hands and each other. Classes on farming, upcycling and mending are core to our program.

Up until recently our low-tech and socially-minded approach to learning didn’t raise any eyebrows in the historically tolerant Dutch education system, but our stated goal of creating a generation of leaders who are radically resilient and know how to survive—even if the complex digital infrastructure and machinery of our lives breaks down—has ignited heated debates about the economy, sustainable farming, education, and the environment in the press.

The thing that really got us in trouble was when we refused to serve analogue meat and dairy substitutes and automated greenhouse vegetables in our vegetarian, student-run cafeteria. Now my school is under attack by parents, politicians, and especially industry lawyers who represent the automated horticulture industry centered around Westland and alternative meat industry based in Wageningen. Both industries sell internationally, and it doesn’t look good when Dutch schools refuse to serve their products.”

Person: The Farmer

WHO: Aleksander

WHAT: Farmer

WHERE: Poland

“I used to grow baking potatoes and soy for animal feed. Now my potatoes get processed into starch which is used to make vegan cheese sold in the cities. To be honest I have never eaten vegan cheese myself, and I am not so sure that I want to. I get annual payments to let my soy fields re-wild and become part of a natural habitat corridor. My biggest source of income is spreading basalt on my fields to soak up atmospheric carbon. It is just some minerals that a truck drops off once a week that end up washing into the ocean, and have nothing to do with me or my land. I enjoy listening to the songs of the species of birds that are returning each year, but I don’t feel like much of a farmer or like I have any freedom to make decisions for myself. My wife doesn’t like to see how the changes to our farm have made me less of an independent man and it sometimes feels like I am just taking orders from a computer or policymaker very far away. Sometimes it feels like these systems value a single insect or bird more than a human farmer.”

Person: The Philosopher

WHO: Elena

WHAT: Philosopher

WHERE: Italy

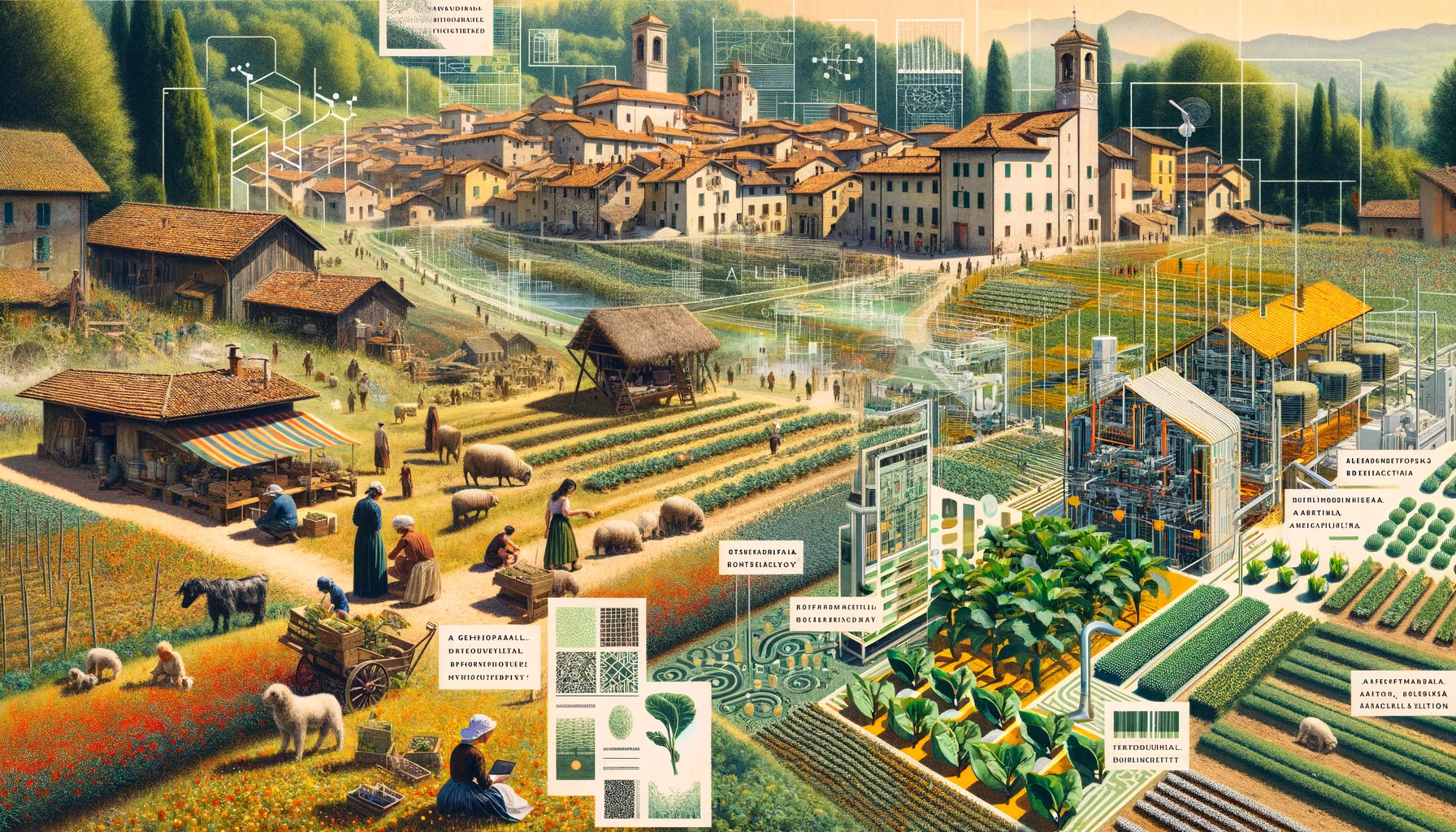

“I had never worked as a farmer, but when the European Commision refused to ban the use of Glyphosate in agriculture—the herbicide known for being carcinogenic—I really became radicalized. I wanted to grow my own healthy food on my own land. But I knew that if this herbicide was going to be used for another decade, I had to put some space between my land, and farms that use Glyphosate. After thinking about this for some time, I wrote an essay called “Air-Gapped Agriculture.” It describes farms that put distance between themselves and any exposure to chemicals and microplastics from industrial agricultural. So that’s what I did! I built a movement in the watershed where I live, where we began air-gapping our land and focusing on the “taste of place” in this bioregion. Now my goal is working with others in Italy to transition as much arable land as possible towards agroecological systems that are less susceptible to exploitation or extraction. While some Air-Gapped Agriculture practitioners embrace traditional methods, others experiment with AI and environmental DNA analysis to monitor biodiversity. This has led to philosophical divisions within the movement.”

Event: Public Plant Breeders Conference: Retainers and Retrainers

The Journalist: “Yesterday I travelled to Berlin to attend the annual Cultivar Collector Conference (CCC). When I arrived, the door was blocked by protesters holding “NO CRISPR IN MY KITCHEN” posters. I flashed my journalist pass and snuck in a side door.

A colleague at the snackbar waved me over: “Did you hear?” she asked, “The Cultivar Collector Community has split into two camps and everyone’s going crazy.”

Over the last year, a deep ideological divide had pitted the cultivar fetishists community against itself. On one side, the “retainers” were zealously preserving heirloom varieties, shunning any form of contemporary genetic engineering; while at the other extreme, the “retrainers” began embracing cutting-edge technologies like CRISPR, transgenesis and spray-on gene editing to create new, open source cultivars. Both groups claim to be the protectors of agricultural biodiversity, so I interviewed members of each to better understand their perspectives.

The CCC niche group of public plant breeders and seed savers arose as a reaction to corporations and governments who put restrictions on plant breeding and seeds. These “restrainers,” as CCC members call them, use proprietary corporate licenses, strict regulation or onerous paperwork to control and privatize biological material.

It became clear that whether CCC attendees saw the future as high-tech or low-tech, they could all agree on a botanical future that was free, open and more biodiverse.

Event: Tv Show – Ideology and The Future of Food

Hi and welcome to this EU supported talk show on the Future of Food here in Belgrade, Serbia.

Host: Hi, and welcome to this EU supported talk show about the Future of Food here in Belgrade, Serbia.

Gaian Gastronomist Contestant: We want to reinvent food as a catalyst for environmental rejuvenation.

Alt Proteins 4 All contestant: We wish the EU would be more supportive. Our automated indoor protein factories are optimized for efficiency and use less land & energy.

Whole Meat Nationalist Contestant: We want meat-heavy, simple food just like grandma cooked and grandpa ate.

Cottage Industrial Ecology contestant: Zero Waste, Infinite Flavour. AI supply chains update every 20 minutes and all outputs are inputs for the next recipe.

Journalist insight: Food is a playground for new possibilities and hybridities, but also a battleground of polarized identity politics.